🗓 30 July 2022

Markets move

No.006 – The pendulum swings

This is a Designance post. Designance is longer form writing that I publish sporadically. I write it as I explore the principles of design and finance. It’s me thinking aloud as I work out the best way to achieve financial independence.

Coming up

- Experience: painful lessons from public and private markets 🔥📉 – ⏱ 4min.

The pendulum swung

It’s been a wild couple of years in “the markets”; first Covid and Quantitative Easing, now inflation and war.

The public stock market began a sustained downward trajectory about 6 months ago and investors have gone from feeling free and easy, to being consciously coy with their capital.

Analysis of a sample of 90 public Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) companies 1 shows that 80% now trade at a value below ten times (“10x”) the amount of revenue they expect to earn in the next twelve months (NTM). For context, the median peak NTM revenue multiple was 50.8x, down to 8.8x today. An 80% drop.

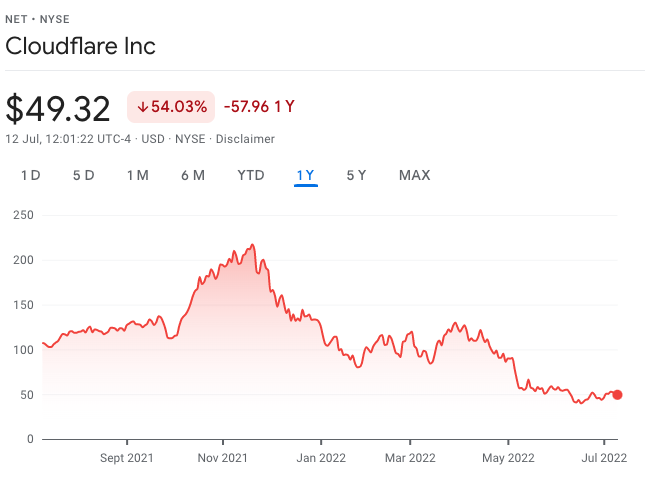

Closer to home, my shares in Cloudflare have been cut by 75% from their peak. My first attempt to “dollar-cost average” (DCA) an investment – that is, buying-in piecemeal over a longer period – couldn’t save me from losing over a third (-36%) of the money I originally put in.

Which is fine. It was money I had to burn and a bit of it got burnt. Markets go up, markets go down and (hopefully) even out over the long term. It’s still an operational business that’s trying to create some value.

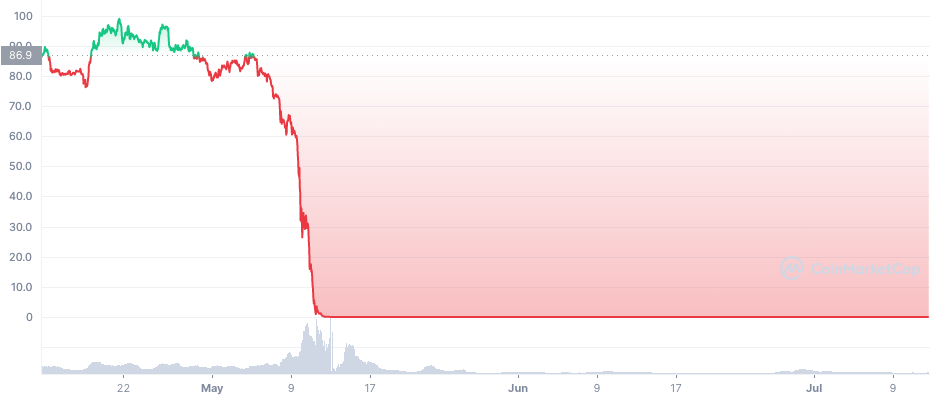

Unlike some crypto:

At its peak, Cloudflare was trading at around 100x its annual revenue. Investors were confident it would grow and make more money (or were happy to wait for 100+ years to get their money back?). Importantly, the inflation-induced correction – or, in this case perhaps, realisation that maybe 100x was maybe a bit overconfident – began creating problems for private companies.

A private company (often) takes investment from private market investors. In return for the risk of investing in (mostly) unproven companies, investors expect a big payout down the line. The public markets usually reward this risk by buying shares at a price far higher than the early investment once the private company goes public.

It’s hard (read: expensive) to own a meaningful share of a private company, so you might be thinking “why do I care?”. Well, it’s surprisingly easy to end up “invested” in a private company; you could be an employee of one.

Private companies that take on investment get that cash in phases; they hit a goal, they get more money. Find a problem; 💰 seed funding. Find a solution; 💰 Series A. Find customers; 💰 Series B. And so on.

Once these companies have traversed as much as the alphabet as they need to, it’s time to raise money in the public market. When the money in the public market gets more skeptical, it puts the onus on the private company to have good “fundamentals”. Startups face more scrutiny. Good companies get lower valuations (to match lower expected returns) and the shit ones simply don’t make it; their employees end up on layoffs.fyi.

A year ago, a job offer from a startup with a 12 month runway (Ie. how long they can continue to pay their bills for) was fine; it was easy to raise more cash later.

You probably didn’t know if the startup would succeed any better than the next person, but while the money was flowing in no questions asked, it didn’t matter; you got paid. If you didn’t, well, there was always a new company to jump to.

Today, considering a job offer from a startup requires you to think much more like an investor:

“Someone looking for an early-stage startup job is actually in the same position as a savvy derivatives trader” (Byrne Hobart] via The Diff).

Ask: is the startup showing signs of promise? Are they building something genuinely valuable? Is a 12 month runway enough? Probably not 2. If the company folds, what value can I take to the next job?

Wild bets on companies and ideas with outside odds are being ditched in favour of boring things that make money today.

Bootstrapped businesses are feeling good; they never needed OPM to get going, never “shot for the moon”, but worked hard at solving valuable (but usually smaller) problems, and got paid.

Under-rated tweet. Note that most of the metrics and (excellent!) presentations are about impossible fundraising, not about flagging sales.

— Jason Cohen (@asmartbear) June 9, 2022

If you're a profitable B2B SaaS business, you're probably unaffected. At least, so far.https://t.co/FK7nDkSIhy

Where’s the excitement in solving small problems?

I guess it’s in bootstrapping your own company…

Footnotes

-

Via 2022 SaaS Crash] ↩

-

The 2008 downturn saw some software companies wait ~3 years before being able to move from survival mode to growth mode ↩

Get notified of new posts

© Jonathan Roberts 2022

I occasionally update articles to fix typos, improve readability or modify content when new information is available to me: view revisions for this article